The Coronavirus pandemic has put the world on pause. As we close our doors, keep ourselves apart from friends and family and stay in-place for an open ended amount of time people are looking to the outdoors and rediscovering local wildlife. As a result of so much time at home, walking around the neighborhood, gardening or visiting natural landscapes, animal rescue facilities are seeing a drastic increase in calls for animal care and inquiries. At the same time the wildlife facilities shut their doors to the public in March of 2020 and let go a large majority of staff and volunteers.

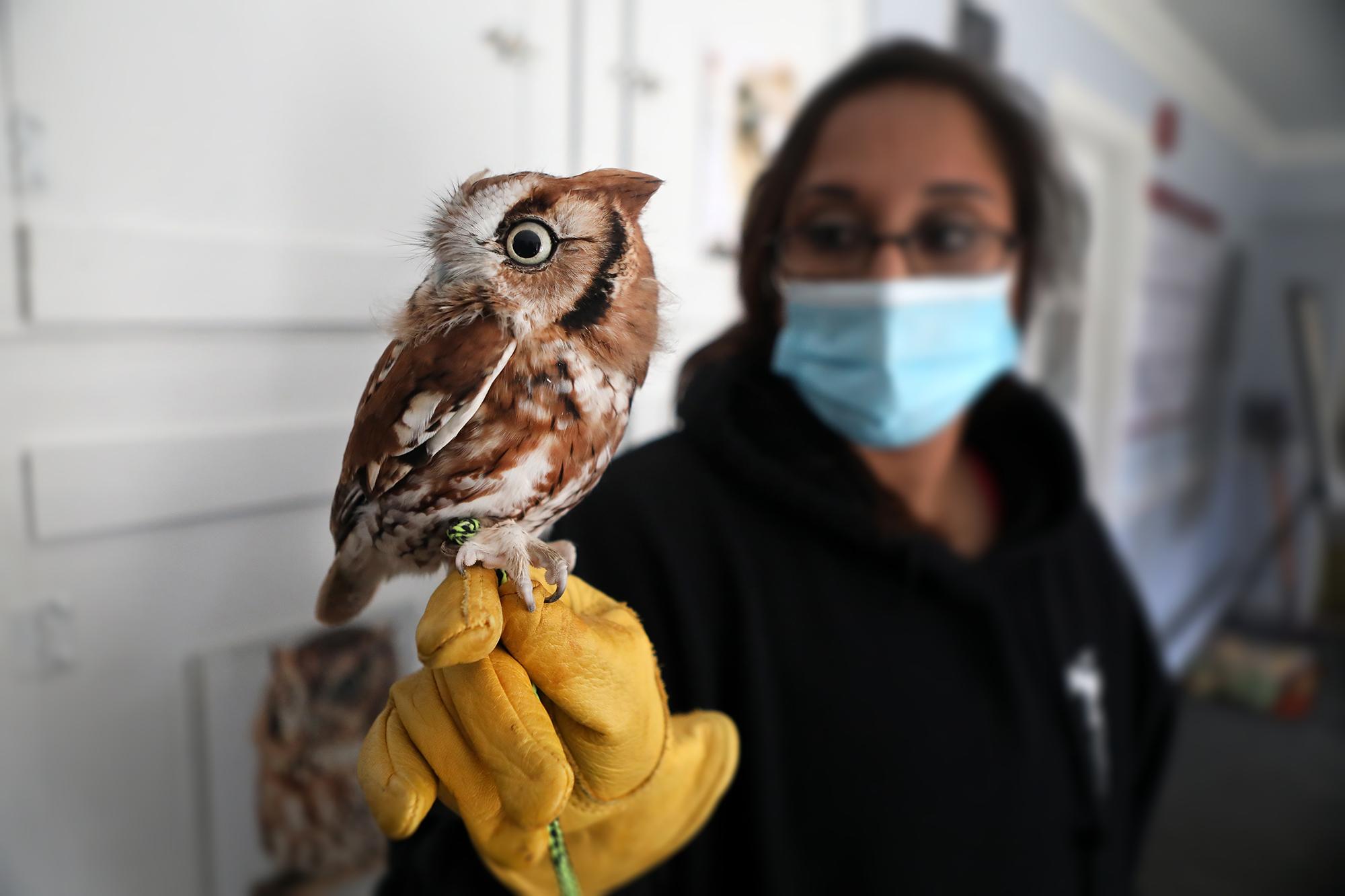

The New England Wildlife Center (NEWC) and the Cape Wildlife Center (CWC) went from operating with over 200 students, volunteers and vet staff to just 6 on-site animal care professionals between the two facilities. The facilities have cared for sum 225 different species. To meet the demand some of the veterinarians are living at the centers in order to care for the 150-or-so animals inside the building at any given time 24-7 and limit exposure to the spreading disease.

'The night before there were 4 rabbits, we heard some loud squealing and today there are only two left,' says Aila Chase, age 11 from Duxbury Massachusetts. Ali and her mother Annabel Chase, found a shallow nest of baby rabbits tucked under a bed of Irises next to the house in their front yard. They called the local rabbit expert recommended by the New England Wildlife Center to provide directions on the best course of action. Together they monitored the baby bunnies, placed them back into the nest and constructed a make-shift fence to protect them from predators, including potential cat and dog attacks. 'I wish I knew more about the rabbits. Now we have an opportunity to learn and we are both learning a lot,' says Annabel.

On averaging since the spring of 2020 over 45 calls each day would flood the phones of the CWC compared to the normal 25 calls per day on average. Zak Mertz, CWC Executive Director, had all incoming calls to the center linked to his personal cell phone. Mertz has heard people wonder if there are more birds since Covid, where they are simply hearing the bird songs without distraction, maybe the first time.

In-home licensed rehabilitators are seeing a huge surge from absorbing the overflow of animals flooding out from the wildlife facilities. Throughout Massachusetts there are 186 wildlife people licensed by the state's Division of Fisheries and Wildlife.

Sue Cowan, an experienced wildlife rehabillitator for 21-years, has both state and federal permits. Because of the overwhelming amount of birds needing care, Cowan made the decision to only take in migratory species since they are harder to place.

Susanna Tuffy, Licensed Wildlife Rehabilitator from Duxbury Massachusetts, can hold around 60 animals a year out of her home and has the capability to care for a wide range of animals including reptiles and most small mammals. This year she had around 100 animals move through her home. 'The licensed rehabilitators are already filling up, we need more of them,' Tuffy says while feeding a baby squirrel. The squirrel was brought to her by the Plymouth Animal Control when he was about 4 weeks old.

Tina Worton from Pembroke and JT McNeil, from Quincy both volunteer their time to rescue wild animals. Worton and McNeil at one point had 30 squirrels, 7 cottontails and 3 opossums between the two of them. 'We have seen a huge increase where it's almost overwhelming to accept more. The wildlife facilities are full and we are getting the overflow. Everyone is full. It's been really hard,' says Worton.

With all of the challenges in-home rehabilitates and wildlife facilities have faced under the cloud of the pandemic, there is also a silver lining of individuals reconnecting with their local wildlife. One year ago people were too busy to spend time caring for or even noticing mots of their natural surroundings, but now, with a little space and quiet 'we' can turn inward to examine our relationship with nature by looking outward and listening to bird songs.